General Information About Mongolia

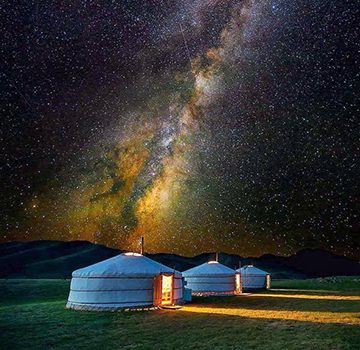

Mongolia, situated in the heart of Asia. Mongolia is the country of grass of the steppes, sand dunes, mountains. Mongolia is a land of nomadizm. Mongolia is the country of blue sky. Mongolia is a remarkable sunny country enjoying 262 sunny days a year. Come to Mongolia with Nomad Nation Adventure and find out what Mongolian hospitality means. You will be welcomed to share the nomad’s fire and food.

Capital Ulaanbaatar (Ulaanbaator, Ulaan-Baator, Ulan-Bator). 1,300,000 inhabitants.

Location

Completely landlocked between two large neighbors – Russian Federation and China. It was immeasurably bigger during the period of Mongol conquest under Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan. Until the 20th century Mongolia was twice its present size and included a large chunk of Siberia and Inner Mongolia (now controlled by China).

Territory

Mongolia is ranked as the seventh largest country in Asia and the 18th largest in the world. Mongolia covers an area of 603,899 square miles (1,564,100 sq. km.), larger than the overall combined territory of Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy. Mongolia is the largest land-locked country. Mongolia lies between 87° 44’E and 119° 56’E longitude and between 41° 35′-44’N and 52° 09’N latitude in the North of Central Asia. The territory of Mongolia extends 1,486 miles (2,392 km.) from the Mongol Altai Mountains in the West to the East and 782 miles (1,259 km.) from the Soyon mountain ranges in the North to the Gobi desert in the South. The nearest body of ocean connected water to Mongolia is the Yellow Sea, 435 miles (700 km.) away in the East.

Boundaries

Mongolia is bordered with Russian Federation to the North, China to the East, South and West. Its total borderline is 5,072 miles (8,162 km.) long, 2,166 miles (3,485 km.) of which is with Russian Federation and 2,906 miles (4,677 km.) is with China.

Climate

Mongolia’s climate is extremely continental. The high central Asian mountain ranges surrounding Mongolia on practically all sides form a formidable barrier against the humid masses of air moving from the Atlantic and the Pacific, thus establishing the dominance of a continental climate in Mongolia. The typical climatic features are sharp temperature fluctuations with the maximum annual amplitudes reaching 90°C in Ulaanbaatar. Even the daily temperature may fluctuate by 20°C-30°C. The coldest month is January. In some regions, for instance in the northern part of the Khuvsgulaimag, the temperature drops to between -45°C and -52°C. Average winter: -24°C. The hottest month is July. On the greater part of Mongolian territory the air temperature rises to 20°C. In the south it is as high as 25°C-30°C. Average summer: +20°C. The mean annual precipitation is 200 – 300mm of which 80 to 90 per cent falls within five months (May to September). Mongolia is the land of winds and especially sharp winds blow in spring. In the Gobi and steppe areas winds often develop into devastating storms, reaching a velocity of 15-25 meters per seconds.

One of the highest countries in the world with one of Eurasia’s highest capitals.Mountains (40%) and rolling plateaus with vast semi-desert and desert plains in the center and a desert zone in the south. Average altitude: 1,580m above sea level. Ulaanbaatar: 1,380m above sea level. The highest point is the TawanBogd (4,374m) in the west and the lowest is the KhokhNuur lake depression in the east – a more 554m above sea-level.

The geography of the country is characterized by great diversity. Mongolia is divided into six basic natural zones, differing in climate, landscape, soil, flora and fauna. The principal mountains are concentrated in the west, with much of this region having elevations above 2,000 meters and the country’s highest peaks permanently snow-capped land covered with glaciers. Mountains and dense forests predominate central and northern Mongolia and grasslands cover large areas of this region. Across the eastern part of the country stretches the vast grasslands of the Asian steppe. The steppe grades into the Gobi desert, which extends throughout southern Mongolia from the east to the west of the country. The Gobi is mostly gravelly, but also contains large areas of sand dunes in the drier areas of the Gobi near the southern border.

The country is dotted with hundreds of lakes, the largest being Uvs-Nuur (covering an area of 3,350 sq.kilometers), Huvsgul (2,620 sq. kilometers), and Khara Us-Nuur (1,852 sq.kilometers). Lake Huvsgul is also the largest fresh-water lake in Central Asia. The Orkhon (1,124 kilometres), the Kherlen (1,090 kilometres) and the Selenge (539 kilometres) are the largest rivers.

Tribes

Chalkha Mongol (85% of population), Kasach (7%), several Mongolian tribes (Burjat, Durwut, Bajat, Dariganga, Dsachtschin, Torgut). Four million Mongols live outside Mongolia.

Traditions and customs

Traditions and customs of Mongols have a wide range of common traditional practices and religious rituals.

Greetings

When a visitor spots or approaches a ger he says “Nokhoi khorio”, which literally means “Tie the dog”. A hostess or a child usually comes out and invites the guest into a ger. The visitor should not carry a whip, hobble or weapon when he comes in and he hangs his knife from the belt. The visitor normally does not knock on the door. He crosses the threshold with the right foot. A guest greets inside, not outside. In Mongolia, the younger usually greets first and asks’ Ta sain baina uu?’ which means, “How are you?” Mongols living in the countryside are not used to shaking hands with visitors; instead, they greet by stretching their arms if they see each other for the first time in the year.

Government of Mongolia

Parliamentary type of Government, with President second in authority to state Great Hural (Parliament).

Independence

1921 final independence from China. 1990 Democratic reform and shift from dependence on the former Soviet Union.

Constitution

It was adopted on January 13, 1992, put into force on February 12, and amended in 1999, 2001 and 2019. The new constitution established a representative democracy in Mongolia, guaranteeing freedom of religion, rights, travel, expression, unalienable rights, government setup, election cycle, and other matters. It was written after the Mongolian Revolution of 1990 and dissolved the People’s Republic of Mongolia. It consists of a preamble followed by six chapters divided into 70 articles.

It is very close to and/or inspired by Western constitutions in terms of freedom of press, inalienable rights, freedom to travel, and other rights.

Previous constitutions had been adopted in 1924, 1940 and 1960.

Administrative subdivisions

21 aimags (provinces), the capital city (Ulaanbaator), including 3 autonomous cities (Darkhan, Erdenet and Choir).The aimags are subdivided into soums, or district of which there are 298. The biggest aimag is Umnugobi which occupies an area of 116,000sq.km but due to its rigorous climatic conditions has the smallest population (only 42,400 people).

Ecology and Environment

Mongolia’s natural environment remains in good shape compared with many Western countries. The country’s small population and nomadic subsistence economy have been its environmental salvation. The great open pastures of its northern half remain ideal for grazing by retaining just enough forest, usually on the upper northern slopes, to shelter the abundant wildlife

However, it does have its share of problems. Communist production quotas put pressure on grasslands to yield more than was sustainable. The recent rise in the number of herders, from 134,000 in 1990 to 414,000 in 2000, and livestock numbers is seriously degrading many pastures. The number of wells has halved in the last decade due to neglect and the health of herds has started to decline.

Forest fires are common during the windy spring season. In early 1996 an unusually dry winter fuelled over 400 fires in fourteen of Mongolia’s twenty one aimags. An estimated one-quarter (about 80,000 sq km) of the country’s forests and up to 600,000 livestock (and unknown numbers of wildlife) were destroyed. Damage to the Mongolian local economy was officially estimated at a staggering US$1.9 billion. Serious fires hit again in 1999 and 2000.

Other threats to the land include mining (there are some 300 mines) and deforestation. Urban sprawl, coupled with a demand for wood to build homes and to use as heating and cooking fuel, is slowly reducing the forests.

Economy

Since 1991, the government of Mongolia has been pursuing on a program of economic stabilization and structural reform, and implemented a broad range of measures to expand the scope of market transactions. Privatization: Comprehensive privatization program was launched in early 1990’s. 100 percent privatization of the live-stock ensured preservation of traditional Mongolian economy. Under the law on privatization of housing, almost 100 per cent of housing has been privatized. Resolution of the property issue through privatization has dramatically decreased government’s involvement in economic life and boosted private initiatives. Currently, the private sector produces more than 60 per cent of GDP. Liberalization of foreign trade: Mongolia is one of the few countries in the world where for 2 years tarrifs and duties on imports, except for some items, have been abolished. Currently, the reintroduced tarrifs are being sustained at the level of 5 per cent. Exports are exempt from taxation.

Due to strict monetary policy, Mongolia managed to curb inflation, which has been aggravated by price liberalization. Thus, considerable progress has been achieved in transforming Mongolia’s economy into a market system.

In 1999, GDP growth was sustained at the level of 3.5 per cent, which significantly backs up stabilization of economic development. Growth was ensured mainly by trade, service, agriculture and mining sectors. Consumer price index by the end of 1999, increased by 10 per cent, but did not exceed 15 per cent. Unemployment rate was sustained at the level of 6 per cent. Budget revenues amounted to 259.4 billion tugriks and total expenditures 344.4 billion tugriks.

Money in Mongolia

Local money is the tugrik. It’s composed of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 1.000, 5.000, 10.000 and 20.000-tugriks banknotes. The face of Genghis Khan or Sukhbaatar is represented on each banknote.

The exchange rate constantly varies. On the 1st of January 2020, 1 euro was 3150 MNT, 1 dollar was 2756 MNT, and one pound was 3920 MNT. You don’t need to change euros in US dollars before coming to Mongolia, euros can be changed directly in Ulan Bator.

Except Ulan Bator and a few other big cities, it’s not possible to use your internation credit card or to withdraw money. You’re adviced to have tugriks with you as soon as you’ll go far from the capital. The Visa card is accepted in more places than Master Card (that is accepted only by the Golomt Bank, Ulan Bator). You don’t need to change money at the airport or the hotel, your guide will come with you to the exchange offices whose commissions are more attractive.

Although Mongolia has a very low standard of living, it remains rather expensive regarding electronic goods, household equipment or farmproduce products. In effects, the country has a very low level of production and is very dependent from the imports.

For your stay in Mongolia, you’re recommended to bring between 100 and 150 euros per person for your personal consumptions. In Ulan Bator, a meal in a good restaurant costs about 15 euros and a beer (0,5 liter) costs between 1 and 1,50 euro (1,13-1,70 USD ; 0,74-1,12 GBP). Cashmere is a solid value. A pullover costs about 50 euros (56,71 USD ; 36,22 GBP), and a scarf 20 euros (22,67 USD ; 14,88 GBP).

Religion

Buddhist Lamaism (94%) since 14th century, Shamaism (in the north), Moslems in the West (Kasach groups).

Traditionally, Mongols practiced Shamanism, worshipping the Blue Sky. However, Tibetan Buddhism (also called Vajrayana Buddhism) gained more popularity after it was introduced in 16th century. Tibetan Buddhism shared the common Buddhist goals of individual release from suffering and reincarnation. Tibet’s Dalai Lama, who lives in India, is the religion’s spiritual leader, and is highly respected in Mongolia.

As part of their shamanistic heritage, the people practice ritualistic magic, nature worship, exorcism, meditation, and natural healing.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Mongolia had hundreds of Buddhist monasteries and about 30 percent of all men were monks. Communists led an anti-religious campaign in the 1930s, which nearly destroyed the extensive system of monasteries. Under Communist rule, atheism was promoted and monasteries were closed, although shamanistic practices survived. From 1945 to 1990, only one monastery (Gandan in Ulaanbaator) was allowed to operate.

Democratic reform that started in 1990 allowed freedom of religion; well over 100 monasteries have reopened, and Qazaq Muslims are allowed to practice Islam. Many young people are receiving an education through these traditional centers of learning, and the people are once again able to practice cherished traditions.

Religion mask dancing “TSAM” in Mongolia.

Language

The script is Cyrillic due to Russian influence but a switch back to traditional script has begin in schools. Second language: Russian is spoken by many graduates, with many Mongolians formerly educated in Russia. English is replacing Russian as the second language. German is spoken by many graduates, and a little Spanish, France and Japanese is spoken. Chinese not widely understood except in border areas.

Literacy

The Mongolian literacy is considered as one of the highest: approximately 90 per cent. Educated working force is already available. Most Mongolians speak and understand Russian as it was compulsory at secondary schools during communism. However, there is an urge for learning foreign languages, especially English, Japanese, Germany among young population.

Education

Until the start of communism, education was solely provided by the hundreds of monasteries which once dotted the landscape. Since 1921, modern Mongolian education has been a reflection of its, dependence on the USSR.

On the one hand, elementary education is universal and free, with the result that Mongolia boasts a literacy rate of between 80% and 90%. Mongolians receive 11 years of education, from ages seven to 17. In remote rural areas where there are no schools, children are often brought to the aimag capitals to stay in boarding schools, returning home only for a two-week rest during winter and a three-month holiday in summer.

The Mongolian State University (originally named Choibalsan University in honour of Mongolia’s most bloodstained ruler) was opened in 1942. In the last 10 years private universities, teaching everything from computing to traditional medicine, have sprung up: the country currently has 29 state and 40 private universities, mostly in Ulaanbaator.

Unfortunately, education standards have plummeted since independence and literacy rates are starting to fall. Economic pressures have forced increasing numbers of students to drop out of school; the percentage of students completing compulsory education fell from 87% in 1990 to 57% in 1995. Tertiary students realise they will have to study abroad to gain a worthwhile, internationally accepted qualification. Corruption among low-paid teachers is reportedly rife; students can virtually ‘buy’ good marks at some universities.

An interesting gender imbalance is opening up in higher education (although if the reverse were the case it wouldn’t warrant reporting); in 1999 over 70% of university students were female. Around 77% of doctors and 60% of lawyers in Mongolia are women.

Distance education has always been important in Mongolia, as so many herders live in remote areas, but economic hardship and higher tuition fees force students to stay at home. A nationwide radio education program, supported by Unesco, teaches nomads everything from marketing skills to how to best care for Bactrian camels.

POPULATION

At present, the population of Mongolia is 3,000,000 (2015) and the population density is 4 persons per square mile (1.5 persons per sq. km). However low population density does not mean that this extensive area of open steppes is an uninhabited place. More than half of the population live in rural areas. 35percent of the total population live in capital city Ulaanbaatar. In 1918, 648,100 people lived in Mongolia. The population of Mongolia reached 772,000 between 1921 and 1950. The population tripled in size from 1950 to 1998. The population density varies considerably by aimags and cities. Some big cities of Mongolia are more densely populated. For instance, density by person per square mile is about 1275 in Darkhan, 369 in Ulaanbaatar and around 2665 in Erdenet. Umnugoviaimag has 63,861 square mile (165.400 sq.km) area and in 1998, its population was 46,200 and the population density was 0.72 person per square mile. This is the largest aimag, which comprises 10,5 percent of the country’s territory, but has the lowest population density. Selengeaimag has the highest population density of 6.7 persons per square mile. Generally, in 1998 population of aimags ranged between 13,100 and 123,600. In Mongolia, the ratio of men and women is about 100.

THE ETHNIC COMPOSITION

The ethnic composition of Mongolia is fairly homogeneous. In 1989, Khalkha Mongols constituted 79 percent of the population, Kazakhs 5.9 percent and other groups constituted the rest. At present, there are 15 nationalities in Mongolia, represented by the following ethnic groups: Khalkha, Durvud, Bayad, Buriat, Dariganga, Zakhchin, Uriankhai, Darkhad, Torguud, Uuld, Khoton, Myangad, Barga, Uzemchin and Kazakh. The percentage of Khalkha Mongols in the ethnic composition increased and the percentage of people of Russian and Chinese ancestry decreased. In recent years the emigration of about 60,000 Kazakhs to Kazakhstan has affected the percentage of Kazakhs in the overall population of Mongolia.

MIGRATION OF POPULATION

In 1956, the urban population constituted 21.6 percent and it increased to 54.6 percent in 1994. The center of urbanization is Ulaanbaatar City, where population growth is particularly high. Migration is especially intensive from the western parts of the country to the center. The Government will have to pay closer attention to the emigration issues if the trend towards the increase is remaining in the future.

POPULATION PROSPECT

It is estimated that the percentage of and the number of children in the population will decrease while the population of working age will increase. Also the number of the elderly is expected to gradually increase. According to rough estimates, Mongolian population will increase to reach 3.4 million in 2019 and the percentage of children of the age below 14 will decline to 27 percent. This also indicates that the population of working age will rise to 10 percent. There was a rapid growth in the birth rate in the 1960s, and the highest ever recorded was from 1970-1980. Since the 1980s the increase has been stable. However, the birthrate has been decreasing since 1990s and its ratio was 20.9 in 1998, which is higher than the world’s average. The death rate is decreasing and in recent years it has been 7.2 which is lower than the world’s average rate.

Nature and Environnement of Mongolia

General information about nature and environnement of Mongolia

Overall, the nature and environment of Mongolia are still in a good state of preservation;

primarily due to late urbanization, nomadic lifestyle traditionally sparing its resources to survive, and very respectful spirituality and harmony with the forces of Nature.

Biodiversity is significant, especially in the North and the West of the country. Air and water are remarkably pure outside the capital city.

Large geographical zones of the country are classified as natural reserves and protected areas. Some have had such status for centuries, so much Mongolians are concerned about their safeguarding.

Nevertheless, natural or human threats are real to these ecosystems, which remain fragile despite their magnitude. 200 vegetable species, 59 bird species and 28 mammal species are in danger or on the brink of extinction.

Frequent spring fires following dry winters as in 1996 had a devastating effect on significant surfaces. The very rigorous and snow abundant winters in 1999 and 2000 caused massive losses not only among domestic livestock but among wild species as well, especially gazelles and antelopes. The last two summer’s drought was alarming by its effect on the water level of rivers and wells. Desertification is taking place in the south of the country threatening to turn the steppes into deserts. The natural erosion of these windy grounds is accentuated by increased pressure on pastures after livestock privatization.

Combined with the high atmospheric pressures, Ulaanbaatar faces with significant air pollution, especially in the winter season, due to emissions of rapidly increasing automobile traffic, smoke from power stations and ger areas heated with fuel and coal.

Despite these threats to its virginity, Mongolia offers an example of inhabited natural environments, exploited but still little impacted by the presence of man, that have become rare elsewhere in the world.

Discover the Mongolia Fauna : Livestock and Wild Fauna

Livestock

It constitutes the most visible part of the abundant animal life and is composed of five species (Mongolians say “the five muzzles”) traditionally raised by the Mongols:

horses for riding and airag (or fermented mare’s milk),

sheeps and goats for meat, milk and wool (cashmere and felt cover for gers),

camels for hair and wool and for pulling the carts,

cows (or more frequently yaks in North) for milk, hair and leather.

Large reindeer herds are raised by Tsataans in the north.

Livestock herds graze freely and are brought back to ger settlements only in the evening. They enjoy semi-freedom and are partially watched over by herdsmen, mainly, to defend from wolves. Sheep and goats are usually packed at night near gers.

Livestock comprises almost 90% of the domestic agricultural industry and animal husbandry and is the principal occupation for the rural population. While the human population is about 2.6 million, there are 34.8 million cattle, sheep, goats, camels and horses in Mongolia.

Livestock equals capital for the rural population and meat is the staple diet. Besides the mining industry, the products of animal origin such as raw cashmer, horse hair, sheep wool, hides, meat and bonedust, and finished garments and products account for a substantial part of annual Mongolian exports.”

Wild Fauna

Apart from the domesticated animals, the most widespread mammal is unquestionably marmot, which perforates the steppes with millions of underground caves. Mongolians adore driving out into the steppes for amateur hunting to taste marmot cooking. Foxes, rabbits, squirrels, jerboas and other badgers also dig the ground or sand.

Wolves are present everywhere on the territory of Mongolia and represent a real threat to domestic livestock and, sometimes, lonely men in the steppes, especially in winter and at the beginning of spring. Their number is stable and is even increasing despite significant hunting by Mongolians and foreign hunters, followers of the great shiver. The possibility of seeing wolves in summer is rare like the chance to see other threatened species such as brown bear (much rarer Mazalai, Gobi’s brown bear), lynx, Saïga antelope, black tail gazelle, wild donkey and wild camel, moufflon and other Argali sheep of Gobi.

Nature and environment associations are successfully working towards nature conservation. Takhi or Przewalski horses, extinct for 40 years, were successfully reintroduced to Mongolia from European (and French) breeding.

Snow leopards are extremely rare. Its remaining population is estimated at few hundreds. Although strictly protected, they remain endangered due to poaching for its fur.

Mongolia is a paradise for bird lovers

Vultures, eagles, falcons, milans, magpies, cranes, corbels and larks are accompanied in summer by swans, geese, pelicans, herons and ducks. There are large colonies of gulls and other sea birds around certain lakes.

In summer, the steppe buzzes with myriad grasshoppers, which are made devour briskly by trouts, and others salmon species of good sizes, which populate the rivers and the lakes. Pike and pole are also abundant in the lakes. With the exception of brackish lakes and Tuul river heavily polluted around Ulaanbaatar, all water ways are very populated.

Fishing is rarely practiced in Mongolia. According to the traditional cosmology, the fish like the insects does not form part of the species that can be eaten by man. Nevertheless, traditions evolve and change and more Mongolians devote themselves to this sport and easily succeed even with rudimentary fishing gear.

Mongolia’s flora of Mongolia landscapes : Forest, Steppes, Meadows, Deserts …

Forests cover approximately 15% of the country’s territory. They consist primarily of pines and birches. They also shelter berry bushes and shrubs like the blueberry and blackcurrant trees and the potentille. Steppes and meadows cover 52% of the Mongolian grounds. In addition to the graminaceous omnipresent ones, the wild wormwood is widespread. Steppes blossom in spring and to a lesser extent in summer with myriad flowers such as edelweiss, gentians, geraniums, eyelets, delphiniums, peas, ancolies, rhododendrons, asters and others transforming Mongolia into an infinite garden.

Deserts (including the famous Gobi Desert) and semi-deserts occupy about 32% of the territory and are covered with sparse vegetation comprised mainly of saxauls and thorny bushes without leaves and with very deep roots.

Dinosaurs in Mongolia : Fossils of bones and eggs discovered in Mongolia

Since the first expeditions of Roy Chapman Andrews (the model of Indiana Jones!) in the early twenties, many rich layers of fossilized dinosaur bones and eggs have been discovered and studied Tyrannosaurus rex, protoceratops, tarbosaurus and others velociraptors haunted the steppes 700 million years ago.

The Natural History Museum of Ulaanbaatar exhibits two remarkable whole skeletons of tarsauborus and saurolophus as well as fossilized nests. Many discoveries found in Gobi are now scattered in museums and private collections around the world.

History of Mongolia

The common natural resource is surface and underground water. The total annual water reservoir of Mongolia is 1,200 billion cubic feet (34 billion cu.m.) and most of it is fresh water. In Mongolia, there are many possibilities of using the water resource properly.

- Ancient Times

- The Birth (Origin) of Mongols

- The Period of the Hunnu State (Hsiung-nu)

- The Period of the Cian-hi State (Hsien-pi)

- The Period of the Jujan State (Rouran)

- The Period of the Turkish State

- The Period of the Uighur State

- The Period of the Kitan State

- The Period of the Mongol Empire

- The Formation of the Mongol Khanligs. The Formation of the Great Mongol State. The Mongol Empire

- Mongolia from the 14th to the 16th centuries.

- Mongolia from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

- Mongolia in the 20th century.

- Mongolia on the Path of Democracy Chronicles

ANCIENT TIMES

There are many traces of the ancient human race in the territory of Mongolia, including archaeological discoveries in the white cave of Bayanlig and stone weapons found in the UranKhairkhan hill of Baatsagaansomon, Bayankhongoraimag. According to these discoveries, it becomes likely that human being lived in the territory of Mongolia almost 700 thousand years ago. There is a hypothesis that Mongolia is a cradle of the very first human race on Earth. This assumption is based on the appearances of Mongols. Mongols had straight black hair, broad foreheads, narrow eyes, thick lashes, short noses, protruding cheek bones, strong chests and narrow waists. Those people were the product of nature and climatic conditions of Mongolia. Skilled labor produced the homo sapiens almost 40,000 years ago. With the increase of wealth and emergence of private ownership, the clan structure collapsed. Wealthy families came to live in aimag structures. Several aimags formed a union of aimags. Power was concentrated among few descendants of wealthy families and heads of aimags.

THE PERIOD OF THE HUNNU STATE

(Hsiung-nu, 3rd century BCE – 2nd century CE)

Mongol, Turk and Jurchen races had been living in the Mongolian territory from ancient times. They alternatively ruled over each other. However the first politically organized community was the Hunnu State. It was the prototype of the states of Mongolia. According to the chronicles, there was a nomadic tribe Khu in the 5th century BCE. The people was engaged in animal husbandry and each tribe had it’s chief cleric. They formed a confederation of tribes. Those were the Hunnu people who became particularly prosperous in the 4th century BCE. The confederation annexed 24 Hunnuaimags. Tumen was named the Khaan of the Hunnu. Tumen belonged to the aristocratic family of the Khian tribe. It was since that period that Khaan ceased to be elected at the conference, but became a dynastic title. Hunnu people fell victims of the aggressive policy pursued by the Ching dynasty, and aimed at expanding the territory to the North. The Hunnus were driven far from the Ordos territory. The Chinese fortified their new Great Wall. TumenKhaan made unsuccessful attempts to unite various Hun aimags and organize the state. TumenKhaan, induced by his young wife, made his son by his youngest wife, the heir to the throne. But his elder son Modun, assassinated both his father and his younger sibling and seized the throne in 209 BCE. The Hunnu State was not a merely Mongol State. It was the first organized State among the nomadic people of the Central Asia. ModunKhaan annexed the territories in the North and West. In 200 BCE he defeated the Chinese. In 198 BCE ModunKhaan concluded a treaty with the Hun State of China. The Hun dynasty of China, thus, recognized the Hunnu State. ModunKhaan conquered western Turkestan and controlled the trade road, which connected the West and East. The Hunnu State developed into a great power. The territory of the Hunnu State extended from the Ordos to the lake Baikal, and from the Khyangan mountain range to the Altai mountain range. However, the Hun Dynasty of China had been consistently pursuing on the “divide and rule” policy, which in the end brought to the break up of the Hunnu State in 48 ???, and further collapse.

THE PERIOD OF THE CIANBI STATE

(Hsiung-pi) (2nd – 4th centuries CE)

The South Hunnu was under a strong Chinese influence and the North Hunnu people moved farther to the North. The remaining 100 thousand families, or over 500 thousand Huns, joined the Cian-bi people, who formed the Cian-bi State. Tanishikhuai (136-181) played an important role in organizing and consolidating the Cian-bi State. The Cian-bi State grew stronger and expanded its territory in the east and occupied the territory stretching as far as to the Korean peninsula. The Cian-bi State was situated on the territory stretching from the lake of Baikal to the Chinese wall, and from the Korean peninsula to the He Tarbagatai. Tanishikhuai divided his State into 3 parts: eastern, central and western. In 181 ?? Tanishikhuai passed away and his son Khelyang took over. The State affairs deteriorated under his rule. The Cian-bi State broke up. However, Kebinen, lord of one of the aimags, gathered over 10 thousand soldiers and reunited the Cian-bi State. In 235 ?? Kebinen died. As a result, in the middle of the 3rd century CE, after his death, the Cian-bi State was divided into the East and West Cian-bi States, and gradually collapsed.

THE PERIOD OF THE JUJAN STATE (Rouran)

The Jujan State is related to the Cian-bi people. Those were Mongolian speaking people. The State stretched on a vast territory of Mongolia, the western part of Manchuria and eastern part of the Uighur autonomous region, in the present Sing-zian. In the 5th century CE in the territory of the Jujan State there was the lake of Baikal in the North, Gobi and Chinese wall in the South, the Altai mountain range in the West and Korean peninsula in the East. The political center of the Jujan State was located at the foot of the Khangai mountain.

THE PERIOD OF THE TURKISH STATE

The policy of the Turkish State was aimed at taking control over the great trade road. By 580’s CE, the Turkish State expanded to annex numerous aimags with people of diverse nationalities. They defeated the Ephtalit State in the West and subdued the Kirghiz people living in the Enisei basin of Siberia in the North. During the period of the Turkish State it’s territory expanded to reach the Korean peninsula. By the end of 4th century CE, the Turkish State was divided into the eastern and western parts. And Uighur people, who were a part of the Turkish State, defeated the eastern Turkish State in 745 CE. Thus the Uighur State became the successor of the Turkish State.

THE PERIOD OF THE UIGHUR STATE

The Uighur State adopted and pursued on the policy of the Turkish State. During this period the Uighur State controlled the great trade road from China to the Middle East.

THE PERIOD OF THE KITAN STATE

Between the 10th-12th centuries, the Kitans took over. They lived in the basin of the Liao river at the eastern foothills of the Khyangan Mountains. The Elui tribe ruled the Kitan State. In 901 Ambagyan of the Elui tribe ascended the throne. The Kitan State occupied the southeast of the Mongolian territory in 924, Bahain and 16 regions in the North of China in 936. However, intertribal discords and feuds undermined the strength of the Kitan State. At the end of 1120’s, the Kitan State collapsed.

THE PERIOD OF THE MONGOL EMPIRE

FORMATION OF MONGOL KHANLIGS

At the beginning of the 12th century, due to various developments in the Mongolian society, several Khanates, or small Kingdoms were formed. Khanates of Khereyids and Naimans were located in the basin of the three rivers and Altai Mountains. Confederation of three Merkid Khanates stretched along the Selenge river in the North. There was a big Khanate of Tatar tribes by the lake of Buir in the East. The Onggud tribal confederation was situated in the South of Mongolia. All Mongol Khanlig was set up in 1130’s, in the form of confederation of Khanates. Khabula, a descendant of a noble Mongol Dynasty, became the first Khaan of the All Mongol Khanlig. After his death, KhabulaKhaan’s grandson Yesugei ruled the Mongol Khanlig. Years of discord and ruthless feuds followed Yesugei’s death in 1170. Confederation of Khanates fell apart. In the long and grue1ing battle for power one man distinguished himself as a man of remarkable will, intelligence and leadership talent. Temujin, the son of Yesugei and great-grandson of KhabulaKhaan, was the man, who was able to unite the Mongol tribes and revive the confederation of All Mongol Khanligs.

FORMATION OF THE GREAT MONGOL STATE

Temujin became the Khaan of All Mongols, and the title “ChinggisKhaan” was conferred upon him. By 1205 All Mongol Khanates had been subjugated by ChinggisKhaan. At the Huraltai (Assembly of Mongol States), held in 1206, it was proclaimed that the peoples of Mongolian ancestry had been united. ChinggisKhaanacsended the throne of the united Mongol States to become the Great Mongol Emperor.

THE MONGOL EMPIRE

The Great Empire of Mongols was founded by ChinggisKhaan. The Mongol Empire reached it’s greatest territorial extent in the 13th century, encompassing most of Asia and extending westward to the Eastern Europe. ChinggisKhaan was a remarkable military leader, strategist and a wise statesman. He passed away at the age of 66. ChinggisKhaan left to posterity a powerful and unconquerable Empire, as well as pride and grateful memories of himself. After the death of ChinggisKhaan, his son Ogodei became the Khaan of the Mongol Empire. Ogodei reigned from 1228 to 1241. The Mongol Empire expanded to comprise northern China, Turkestan, Middle East, Russia, Ukraine, Caucasus and Iran. Batu, grandson of ChinggisKhaan, reached Hungary Poland and Moravia in 1241-1242. Another grandson of ChinggisKhaan – KubilaiKhaan – conquered the whole territory of China and became the founder of the Mongol Dynasty in China. The Mongol Empire existed for almost 150 years, up to the end of the 14th century.

MONGOLIA FROM THE 14th TO THE 16th CENTURIES

The Mongol Empire declined at the end of the 14th century. Nevertheless, the Mongol Empire remained in the form of confederation. It controlled the territory stretching from the Khyangan Mountains in the East, up to the Irtish and Enisei rivers, from Tengri Mountain in the North, the Great Wall of China in the South. The last Emperor of the Mongol Dynasty was Togugan Timor. In the early 15th century, Mongolia was divided into two separate parts, which led to further break up of the Empire. Dayan Khaan( 1464-1543) ascended the throne in 1470. His efforts aimed at reunification of All the Mongols had failed.

MONGOLIA FROM THE 17th TO THE 19th CENTURIES

The period that started from the end of the 15th century and lasted for nearly 3 centuries, can be referred to as era of the Manchu domination in Asia. The Manchu was a highly militaristic State, that attacked and subjugated Mongolia. Ligden, the great grandson of Batu-Mongke Dayan Khaan, who was the last direct descendant of ChinggisKhaan, was defeated. After having conquered the Tsahar State in 1636, Manchus took Inner Mongolia under their control. In 1644 Beijing was occupied. Mongolia was divided, and the Khalkha Mongols and Oiryid Mongols waged wars against each other. At the meeting initiated by UndurgegenZanabazar, feudals representing the Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia, took a decision to seek protection of the Manchu State. Thus, Mongolia came under the full control of Manchus. The Ching Dynasty established it’s rule and laws over the entire territory of Mongolia. The Manchus consistently pursued on the policy aimed at maintaining disunity of Mongol aimags. Numerous attempts to throw off the Manchu yoke were undertaken by Mongols. The last unsuccessful uprising in 1755-1758, was led by the Oiryid Mongolian Prince Amarsanaa. The Manchu tyranny was to last up to the 20th century.

MONGOLIA IN THE 20TH CENTURY

MONGOLIA BY THE EARLY 1900s: THEOCRATIC STATE

After many attempts to restore independence of Mongolia had failed, Mongolians, desperate to throw off the Manchus, appealed to Russia for aid. In 1911, a meeting was convened in JikheKhuree (present Ulaanbaator), at which Bogda, the Grand Lama, and noble men from the Inner Mongolia decided to send a delegation to Russia. However, the mission was unsuccessful. In November of 1911, Bogda, the Grand Lama, was urged to declare independence of Mongolia, and provisional government was formed. The provisional government was headed by G.Chagdarjav, speaker of Tusheet Khan aimag, and consisted of seven members, including Prince Ts. Khanddorj and G. Tserenchimed, the high lama. The govemmnet led the national liberation movement. By the end of 1911, the Manchu viceroy in JikheKhuree was forced out, in the early 1912, Uliastai, another important administrative post, was liberated. Liberation of the western part of Mongolia in the summer of 1912, created conditions for the overthrow of the Manchu rule in the whole territory of Mongolia. BogdaJavjandamba became a monarch, and declared independence of Mongolia. In the South, the Manchus were defeated by the Chinese. The Chinese Republic, established in 1912, was headed by president da Juntan Yan-Shi-Kai. It refused to recognize Mongolia’s independence. In 1914, three-party talks to include delegations from Mongolia, Russia and China, were launched. These talks, known as Khyagta meeting, dealt with the political status of Mongolia. As a result of these talks, a tripartite agreement was reached, according to which Mongolia was split up, to form Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia but remained independent.

REVOLUTIONARY EVENTS OF 1919-1921

Russia’s revolution of 1917 had a great impact on events in Mongolia. Russian Czarist General G. Semenov initiated a conference, at which the formation of pan-Mongolia confederation was declared. The confederation was to consist of Inner and Outer Mongolia, Barga and Buryat Mongolia. Mongolian government was not represented at this conference. Nevertheless, Chinese military troops, headed by General Hsu-Shi-Chang, were deployed in JikheKhuree. Mongolia’s autonomy was abolished in November, 1919. Revolutionary events in Russia inspired spontaneous uprisings in Mongolia. Two underground political groups were formed, which in June of 1920 were organized into the People’s Party of Mongolia. One of the leaders of the liberation movement – D.Sukhbaatar – formed the people’s army of Mongolia and liberated JikheKhuree from Baron Ungern, in July 1921. By 1922, the entire territory of Mongolia was free from foreign occupation, and the people’s government was formed.

YEARS OF POLITICAL REPRESSION

In 1920s, after the death of the BogdaKhaan, Mongolia had a real

alternative to repressions and executions, that followed the

revolutionary events. The idea of development along the path of national

democracy was extremely popular among many leaders of the Mongolian

People’s Party (MPP) and government. However, the influence on the part

of Komintern and Bolshevik government in Russia was overwhelming.

In August of 1924, the third Congress of the MPP adopted a communist

type program, thus condemning the country to many years of political

terrorism and later on stagnation and political inertia. The first

Deputy Prime Minister S. Danzan and others, who stood in opposition to

the majority’s views, were executed. This marked the beginning of witch

hunting in Mongolia.

Many prominent leaders, including the Prime Minister B. Tserendorj, Deputy Prime Minister A. Amar, Chairman of the MPP’s Central Committee, and T. Tseveen fell victims to Stalinist type repressions. Repressions against religion and lamas were especially severe. Between 1937-1939, over 700 temples and monasteries were destroyed,’ and over 17,000 lamas and monks executed. Political massacre continued up to 1941.

MONGOLIA DURING THE II WORLD WAR

In 1930s, when fascism in Europe and Asia became a real threat, Mongolia signed a Protocol with the Soviet Union, on rendering military assistance in case of insult by a third country. Undeclared war started on 28 May 1939, when Japanese troops attacked Mongolia’s borders in the area of the Khakhyn-Gol. Pursuant to the provisions of the Protocol, Soviet troops were brought up to the border, and Mongolian-Soviet joint forces stopped the invader in August, 1939. The tripartite negotiations held between Mongolia, Soviet Union and Japan in 1940, settled the border disputes. When in June 1941 the Nazist Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Mongolia offered a helping hand to the Soviet people. Domestic resources were mobilized and sent as aid to the Soviet Red Army. At the Yalta conference held in February, 1945, the leaders of the Soviet Union, USA and UK agreed to the existing status quo with regards to the Outer Mongolia.

YEARS OF SOCIALISM

After the II World War, Mongolia adopted the Soviet five-year-plan pattern in the economic policy. In 1958, 99.7 percent of the country’s total livestock was nationalized. In 1960, the Constitution was revised to proclaim a single political party monopoly, single form of property and communist ideology.

Mongolia remained one of the most closed countries in the world up until 1990s. Politically, the country was a satellite of the Soviet system. Economically, Mongolia was heavily dependent on Russian subsidies. Distortions in the economy and inefficient governance brought the country to social, economic and political stagnation.

MONGOLIA ON THE PATH OF DEMOCRACY

With the brake-up of the socialist system, deep political and economic reforms were launched in Mongolia to mark the beginning of the country’s transition from a centrally planned system to a market economy. Mongolia adopted democratic norms and principles through introduction of multi-party, parliamentary system. In 1990s, for the first time in the country’s history, democratically elected government approved the program for transition towards the market. Privatization of the state-owned property and the policy of liberalization were launched. Mongolia declared the policy of open doors. Since 1991, the government of Mongolia, has been pursuing on a program of economic stabilization

The Capital of Mongolia “Ulaanbaatar”

Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, is the main gate for trips to any destination within Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar is located on the bank of the Tuul River and surrounded by four sacred mountains. Well-known as a sunny, peaceful and open city, Ulaanbaatar is a city of contrasts where modern life comfortably blends with Mongolian traditional lifestyle.

Ulaanbaatar city is situated in the foothills of the Khentii mountain range. It is situated in the valley of the Tuul River, which flows from east to west in this location. Mountains and hill slopes define the northern (ChingelteiUul) and southern (BogdUul) limits of the city. There are also mountains to the east (BayanzurkhUul) and west (SonginoKhairkhanUul), but the river valley and its tributaries provide some open land in these directions. Ulaanbaatar experiences an arid continental climate and has four distinctive seasons: summer, autumn, winter and spring. The summer extends from June to August when the average temperature is 15oC. Snowfall starts intermittently towards the end of the autumn. Winter extends from December to the end of February and is mostly cold with the average monthly temperature in February being –19oC. The minimum temperature reaches (minus) – 40oC during this period. The rainy season is from June to August, when about 74 percent of the annual rainfall occurs. The average annual rainfall for the last 20 years is 267 mm. The rapid population growth of Ulaanbaatar city located in the sensitive ecosystem adds to its vulnerability to natural hazards. Population of Ulaanbaatar city has been growing rapidly, due to mass migration of people from natural hazard prone rural areas to the city. Comparing with historical maps one can see the dramatic increase of urbanization and expansion of settled areas along the river basins and flood prone zones because of the intensive migration from rural to urban area of the last few years (Figure 1). Since 1986 the population of the city has nearly doubled. Existing statistical data shows that there was an increase in the number of poor people living in Ulaanbaatar till 2001. However, for the following years, which have had more intensive rural to urban migration, data on poverty is not available.

History of Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar the capital city of Mongolia, is the political, economic and cultural centre of the country. The city was founded in 1639.

The name of the city has changed for several times. It was initially named

URGOO in 1639-1706,

IKH KHUREE in 1706-1911,

NIISLEL KHUREE between 1911-1923, and renamed as ULAANBAATAR right after the proclamation of the Mongolian People’s republic in 1924

URGOO

Formation of the Mongolian Capital has a trace from XVII century. In the year Yellow Rabbit by lunar calendar, exorbitant and influential noblemen proclaimed Zanabazar, son of the Tusheet Khan Gombodorj who was one of the 4 lofty noblemen as the Mongolian Buddhism and built a special monastery complex for him. It was more palatial-like than monastery. Later, Urgoo (means palace) had been

developing as Zanabazar,s reputation and influence grew in the Mongolian social life.

IKH KHUREE

Returning home from Tibet in 1700, Zanabazar started extending Urgoo as the Mongolian religious centre. In 1706, under an order of Zanabazar was built a temple; Battsagaan; in the place named ErdeneTolgoi, and it was the foundation of the IkhKhuree (means Big Circle). Although, IkhKhuree had been stretching, its location had been changed several times.

Thus, IkhKhuree moved 17 times within 30 years period, even twice a year. The repeated moves, of course, delayed significantly the IkhKhuree’s development. Researcher’s survey shows that the transition process of IkhKhuree from nomadism to settlement basically finalized in 70 years between 1706-1778, and urbanization process is considered to be started from the very time.

In 1855, IkhKhuree removed to the Selbe valley, where residents started building

numerous monasteries and temples, in particular building firm and sturdy construc-

tions and houses, which more suited to settled civilisation.

NIISLEL KHUREE

In the wake of the struggle for liberty by Mongolian people Manchu ambassador Sando was exiled and in 1911, a ceremony for the proclamation of the BogdJabzundambaKhutugtu as the Theocratic Monarch and the Head of the revived Mongolian State was took place in IkhKhuree.

ULAANBAATAR

The first State Congress, convened in 1924, passed a decision on October 29 to rename NiislelKhuree as Ulaanbaatar, legalizing its status as the Capital of the

Mongolian People’s Republic.

The “Law on Capital’s Legal Status; was enacted just prior to the 355th anniversary of the city’s establishment. The Capital city carries out its independent urbanisation, socio-economic and it possesses its own flag and symbol”, was indicates in the law.

ChinggisKhaan (Sükhbaatar) Square

In July 1921 in the centre of Ulaanbaatar, the ‘hero of the revolution’, DamdinSükhbaatar, declared Mongolia’s final independence from the Chinese. The square now features a bronze statue of Sükhbaatar astride his horse. In 2013 the city authorities changed the name from Sükhbaatar Square to ChinggisKhaan Square, although many citizens still refer to it by the old name.

Peaceful anti-communism protests were held here in 1990, which eventually ushered in the era of democracy. Today, the square (talbai ) is occasionally used for rallies, ceremonies and rock concerts and festivals, but is generally a relaxed place where kiddies drive toy cars and teens whiz around on bikes. Near the centre of the square, look for the large plaque that lists the former names of the city – Örgöö, NomiinKhuree, IkhKhuree and NiislelKhuree.

The enormous marble construction at the north end was completed in 2006 in time for the 800th anniversary of ChinggisKhaan’s coronation. At its centre is a seated bronze ChinggisKhaan statue , lording it over his nation. He is flanked by Ögedei (on the west) and Kublai (east). Two famed Mongol soldiers (Boruchu and Mukhlai) guard the entrance to the monument.

Behind the Chinggis monument stands Parliament House , which is commonly known as Government House. An inner courtyard of the building holds a large ceremonial ger used for hosting visiting dignitaries.

To the east of the square is the 1970s Soviet-style Cultural Palace , a useful landmark containing the Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery and several other cultural institutions. At the southeast corner of the square, the salmon-pinkish building is the State Opera & Ballet Theatre . Just south of the Opera House is the symbol of the country’s new wealth, Central Tower , which houses luxury shops including Louis Vuittan and Armani.

The bullet-grey building to the southwest is the Mongolian Stock Exchange , which was opened in 1992 in the former Children’s Cinema. Across from the Central Post Office is a statue of S Zorig , who at the age of 27 helped to lead the protests that brought down communism in 1990 (and was tragically assassinated in 1998).

Gandantegchilen

Most Buddhist Monasteries in Mongolia were destroyed during the communist regime, which lasted until 1990. One of the only to survive was Gandan Monastery, being used as a showcase for visitors. It’s official name is GandantegchinlengKhiid, or in Mongolian script. This name signifies something like Great Place of Complete Joy or Great Way to the Cosmos. Literally it can be translated as:

– Gan = rejoyce

– Dan = perfect

– Teg = vehicle >Tegchin = Mahayna (Greater Vehicle)

– Leng = island

Which would result in Mahayana Island of Perfect Rejoice, with Island being a generally used metaphor for monastery.

Gandan is the largest and most important monastery of Mongolia, with over 400 monks.

Inside is a statue of MagjidJanraisig (the lord who looks in every direction). It is about 25 meters tall and is covered by a huge number of precious stones. Notice someone going round the stupa on the right.

The official name GandantegchinlenKhiid, translates into Mahayana Island of Perfect Rejoice, with Island being a generally used metaphor for monastery.

History

The first temple of Gandantegchinleng Monastery was established in 1835 by the Fifth Jebtsundamba, the highest reincarnated lama of Mongolia. In the following years temples for daily service, veneration of Avalokiteshvara and colleges of Buddhist philosophy, medicine, astrology and tantric ritual were established. In the beginning of the 20th century Gandantegchinleng Monastery was the centre of Buddhist learning in Mongolia. Many prominent Buddhist scholars in Mongolia as well as in Buddhist world were educated and trained by its various colleges and their works on Buddhist philosophy, linguistics, medicine, astrology and tantric practice became the most authoritative and accurate Buddhist texts.

During 30s the socialist government adopted a policy of banning all religious activities in Mongolia. As a consequence all monasteries were closed and monks were executed, jailed and disrobed all over Mongolia. In 1938, Gandantegchinleng Monastery was closed, but reopened in 1944 as the only functioning monastery during the socialist regime. After the democratic change took place in 1990 Buddhism regained its full right of worship. Gandantegchinleng Monastery has, as being the Centre of Mongolian Buddhists, been striving to propagate peaceful teaching of Lord Buddha among family and society. In the whole country 140 monasteries and temples have been (re)established and many sacred statues were reconstructed so far.

The Present-day Monastery

Currently Gandantegchinleng Monastery has over 400 monks; a Mongolian

Buddhist University (established in 1970); three colleges of Buddhist

philosophy; a Medical and Astrological College; a Kalachakra temple; a

Jud Tantric College and an Avalokiteshvara (MigjidJanraisig) temple.

The monastery complex consists of Zanabazar Buddhist University, three

temples for Buddhist service and veneration of Avalokiteshvara, three

Buddhist Colleges of Buddhist Philosophy, College of Medicine and

Astrology and two Tantric College. The brief introduction of above

mentioned temples and colleges are given in the below.

The Zanabazar Buddhist University was founded in 1970 and concentrates on Buddhist Studies and Indo-Tibetan Studies. Not only Mongolian students from all over Mongolia but also foreign students study in Zanabazar Buddhist University.

Temples

- Gandan temple is the first temple in Gandantegchinleng Monastery and was established in 1835. Grand services take place in this temple.

- Vajrapani temple was established in 1940 and daily services are performed here.

- Avalokiteshvara temple was built in 1912 and the icon of this temple is the BoddhisattvaAvalokiteshvara (MigjidJanraisig) with a height of 26,5 metre that was rebuild in 1996 under the leadership of current Prime-Minister Enkhbayar.

Colleges of Buddhist Philosophy

- Dashchoimphel was established by II Jebtsundamba and follows the tenet of GunchenJamyanShadba, Tibetan monk scholar of Gelugpa tradition.

- Gungaachoiling was established in 1809 and follows the tenet of BanchenSodnamdagva.

- Idgaachoinzinling was established in 1910 and follows the tenet of Sera Jebtsunba.

- College of Medicine and Astrology trains students in Mongolian traditional medicine and astrology.

- Jud Tantric College and Kalachakra Tantric College prepare students in Buddhist tantric ritual as well as knowledge of tantric practice.

Zanabazar Museum of Fine Art

Zanabazar Museum of Fine Art in Ulaanbaatar was founded in 1966. Visitors can enjoy works of Mongolia’s famous artists, and sculptors who lived before or in the early 20th century. Sculptures by Mongolia’s first BogdKhaan and famous sculptor Zanabazar (“Five Gods” and “Taras”), as well as appliques and sculptures in wood and stone by talented Mongolian craftsmen are among the 10 thousand exhibits of the museum. 25 of the 45 most precious works of art created by Mongolia’s artists can be found in the museum.

The Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts has an excellent collection of paintings, carvings and sculptures, including many by the revered sculptor and artist Zanabazar. It also contains other rare – and sometimes old – religious exhibits such as scroll paintings (thangka) and Buddhist statues, representing the best display of its kind in Mongolia. A bonus is that most of the exhibit captions in the museum are in English.

At the top of the stairs is a glass folder with a detailed explanation of Zanabazar and his work. There are some fine examples of the sculptor’s work including five Dhyani, or Contemplation, Buddhas (cast in 1683) and Tara in her 21 manifestations.

Also worth checking out are the wonderful tsam masks (worn by monks during religious ceremonies) and the intricate paintings, One Day in Mongolia and The Airag Feast, by renowned artist ?. Sharav. These depict almost every aspect of nomadic life. The ground floor has some copies of portraits of the great khaans (kings) and some 7th century Turkic stone carvings.

Nomads Cuisine

Food and diet are an integral part of the Mongolian culture, which

takes its origin from Huns’ time. The stories about Mongolian

traditional cuisine probably will dispel one’s perception that “Nomadic

people in Mongolia eat only meat after de-sectioning a carcass meat to

bone ratio and boiling it.”

Anyone will agree that cuisine or dish of any nation has close relation

to the richness of their culture, nature and geography and practice of

earning for living. Mongolian traditional cuisine has been enriched with

cooking tradition of many other nations which is tracked with history

of the nation 800 years ago, the time of the conquest. As a result of

the conquest, which led to rapid culture exchange and integration of

nations Mongolia was quick to embrace cuisines from other parts of the

world.

That is why today Mongolia is a country with a rich cuisine which combines and presents cuisine of many other nations.

Today, in Ulaanbaatar one can easily find a place to eat cuisine of any

nation, since 60 restaurants of over 20 countries operate in

Ulaanbaatar.

Mongolians have developed many different strict techniques of preparing

and cooking food. Let me share with you an interesting story about the

techniques of slaughtering an animal. Uguudei, one of the

ChinggisKhaan’s sons ordered to slaughter an animal by slitting the

belly and yanking the vena cava. Since then Mongolians use this

technique to have the most nourishing and nutritious meat. Mongolians do

not eat meat all year around. Traditionally, for their choice of food

Mongolians used to take into the consideration what season and how

healthy was the food for that particular time. In the severe winter,

they regularly consume highly nutritious reserved meat rich with protein

and fat to allow them to keep their warmth and stay strong. However,

during the harsh spring, they do not slaughter an animal for food but

prefer to consume borts (dried meat), hyaramtsag (frozen in the casing

blood and other by products), uuts (preserved meat) and shuuz (preserved

meat in its own sauce) and prepare their stomach for the warm summer

time. In the summer, they do not eat meat at all, often consume dairy

products only. When the weather cools down with the start of the autumn,

ripened wild berries, vegetables and grain and wheat come to the menu.

This time I would like to bring you to the traditional cooking of

Mongolia. The restaurant “Modern Nomads” shares their menu with you.

Like Americans love Coca Cola, and Russians kvass, the most favorite

drink of Mongolian people is airag, self-fermented Mare’s milk, which is

considered to be cream of all food and drink. This is a whole milk

curdled to beverage or custard-like consistency by lactic-acid-producing

microorganism. Best time for airag fermenting is the autumn time, not

only because of the warmth but also due to the grass and herbs the

animal eat. One who tried airag in autumn time will remember the

taste-refreshing, but a bit sour. It can not be confused with the milk

we add into a tea. Mongolians consume the tea, which was described by

Marco Polo, a great traveler, that “he felt this drink was I ike an

ordinary drink but left him filled as if he had eaten a light, but

nutritious meal” When you come to any family, the first thing you are

offered is a tea. Mongolians make different types of drinks with milk,

varying in milk content in it, such as hyaram (boiled water with a small

portion of milk to make it look not creamy but milky), tsiidem (boiled

water with even smaller amount of milk to make it look watery, rather

than milky).

Let us now move to the menu. It should be pointed that the recent years

restaurants have stopped to offer fat dish as the customers have become

conscious about the harmful ness of an excess fat and are paying

attention to cook daily traditional menu with lessfat.

1.Huushuur: (Cornish pasties-like, deep fried flat dumpling stuffed with meat) with garnish: Russia and China are two big neigh bors.withwhichthe country had great extent of exchange and some influence on our culture. It is said thatthis dish originates from China, but it is known that this stuffed meat had been popular in Mongolia from very early time. Minced or chopped meat is seasoned with onion, other spices or flavoring ingredients. If one finds huushuur with garnish in the menu, you can have 4-5 hot huushuur arranged with some salad or starters. The meat produces a lot of juice, as being stewed.

Recipe: Divide the pastry into small round pieces and roll them in an appropriate thickness. Before this, minced meat is seasoned. Then place a thin layer of the prepared meat on the one half of the pastry, be careful not to have too much filling which would cause the pastry to burst during the cooking process. Then fold the other ha If over the filling and squeeze the edges firmly together. Start from the right side using first finger and thumb turn the edge over to form a crimp. Repeat with the remaining pasties. While you prepare huushuur put on a frying pan with some cooking oil, heat it until the temperature raises enough to fry the huushuur. Huushuur is fried for 5-10 minutes depending on the temperature. Be careful not to heat the oil too much, then the meat cannot be cooked enough although the pastry is burnt.

2.Milk tea with dumplings: It is one of the popular dish people perceive as a good way of helping one to recover from a fatigue. Dumplings specially prepared for this cooking makes the tea with milk more tasty. If the tea is made to help one to revive strength, usually mutton is minced for dumplings and they put 7 mutton dumplings into the tea, while tea is getting ready. Each region or ethnic group has their own specific recipe for this dish; I will share with you the popular recipe.

Recipe: Weak green tea is made, and then fresh milk is added. The meat minced. Then pastry is prepared, divided into much smaller rolls than huushuur and flattened as described above for making huushuur, but much smaller, be careful not to make it too big or too thin. Small amount of meat is placed on the flattened pastry on the one half, fold the other half of pastry over the filling and squeeze the edges firmly together.

3.Buuz: A kind of Mongolian ravioli steam cooked is a traditional dish offered in big plates to the guests during the festive time. Buuz is cooked for special occasions and also belongs to stew dish menu. Buuz have different names depending on their size.

Recipe: Mincing is made manually, and seasoned. Seasoned meat is placed in the pastry prepared as the same as for dumplings and edge of the pastry is pinched to make a ball-like shape. Then they are put in the steam saucepan for 15-25 minutes, depending on the size and whether they were frozen or not. The person making the buuz has to work a lot being careful to make them the same shape and look fine. As a stew some juice is produced inside the pastry. Nourishing.

4.Horhog and Boodog: it is known from the history that the stew was one of the main technique of cooking of nomadic Mongolian people. Pans and saucepan or pots were introduced only 200 years ago. Before this invention, people cooked the meat using animals’ own skin as a cooking utensil. Meat was taken out of the skin through only opening in the head of the animal, and then the skin was used for the delicious meal with specific technique called boodog, which is offered to the respectable guests. Nobody teaches how to do it, but Mongolians can cook it.

5 most consumed traditional drinks of Mongolia

Travelling is going to discover another culture and different ways of life. With this in mind, tasting the culinary specialities of a country is a real part of the travel. While travellers often worry about food, they forget drinks. Yet, Mongolians have many specialities the traveller can taste all along his/her stay. This is a little list.

The airag, or fermented mare milk, is certainly the drink that best symbolizes Mongolia. If you Airag is made from fermented mare milk mixed with ferment from the year before in a big cow skin bag (khökhüür) and then beaten. This gives an acid-taste drink, very refreshing and very little alcoholic (about 2 to 3% alcohol). Airag is prepared during all June. The new airag must be ready for Naadam, because Mongolians will drink it in great quantities. If you have the good luck to discover the country during summer, you’ll have many opportunities to taste this special beverage. When you’ll be proposed some, you’ll have to be polite and take it with your right hand,the left hand holding your right elbow, wrist, or hand. Then you’ll put the cup to your mouth. If you don’t like it, you can just tell it and give the cup back to the host.

The Suuteitsai or tea with milk is the most consumed drink of Mongolia and you will be proposed some each time you’ll visit a Mongolian family. Once in the yurt, it’s the first thing you’ll be proposed, and you’ll have to accept the cup with your right hand (in the same way as for airag) and put it to your mouth before putting it on the table.

The tea with milk is made with cow milk mixed with water and black tea leaves. It’s lightly salted and sometimes serves as base for a soup, for example banshtaitsai, tea with raviolis inside.

The Arkhi or milk vodka is the Mongolian traditional vodka. It’s distiled with fermented tarag (cow milk yogurt). The acider the yugurt is, the higher the alcohol range will be, about 15 to 20%. All nomads families have their own still. This alcohol is generally made in summer but it gets drunk all along the year. Monglians like to drink it when it’s still hot, straightaway after distillation. As for airag, you’ll have to take the glass you’ll be proposed, with your right hand, and at least put it to your mouth.

Vodka. It’s difficult to talk about the most consumed drinks of Mongolia without evocating vodka. Vodka is not a traditional drink, since it has been imported by Russians during the communist period, but it is today the most consumed drink of the country. Each Mongolian drink about two bottles per month, and the country has hundreds of distilleries. The Mongolian vodka is made with wheat and there are many breands. Most famous are Black Chinggis, Gold Chinggis, Bolor, Soyombo, or KharSuvd. The alcohol level is about 36%. The acceptance ritual of vodka is the same as for airag or arkhi. Let’s tell that each time a family will invite you, there will traditionally be three services of alcohol. With a single glass, the host will serve each guest one after the other, beginning with the oldest one. The guest will at least put the glass to his/her mouth, then give it back to the host, and the latter will fill it again, adding just a symbolic drop if you did not drink anything, and give ot to the following guest.

You’ll certainly note that very often, instead of putting the glass to their mouth, Mongolians only soap their right ring-finger in vodka, then three times above their head, make offerings of alcohol to spirits by making a sort of flick with their thumb and ring-finger.

The Chatsarganiishuus or sea-buckthorn juice is the favorite juice of Mongolians, whether it be cold or hot; it can be considered as the “orange gold” of Mongolia.

Mongolians make boil this berry in water and consume great quantities in juice or tea.This berry is the piece of fruit the richest in vitamin C (eight times more than a kiwi). It naturally grows in the province of Uvs, West Mongolia.

Some industrial productions can be found in Ulan Bator, this berry being also used in many cosmetics. Its fragrance can sometimes displease but the taste is really very interesting. The concentrated juices that we sometimes find in shops often have a too strong taste and can be diluted with water.

Restaurant in Ulan Bator

During these last few months, the supply regarding restaurant industry quickly grew in Ulan Bator. Nowadays, we can find excellent gourmet restaurants and specialities from the whole world: Italian, Indian, Mexican, Japanese, Lebanese and of course Korean. Unfortunately, some chains like KFC or Pizza Hut appeared too.

Arts and Culture of Mongolia

MONGOLIAN MUSIC

With Mongolia’s historic shift to a market economy and democratic

society, the nation’s approach to the arts changed. The culture and art

community was not prepared to face the new trends. This brought a few

years of practical collapse of the arts.

But with the changes, a new approach to national folk music, especially

to the disappearing unique songs and music of Mongolian tribes, was

initiated on the part of the Government of Mongolia. A project was

implemented jointly with UNESCO to audially and visually document the

oral music heritage of the Mongols and set up a national fund of

recordings, which now resides in the National Archives. The most

successful performance groups at the moment are the TumenEkh Ensemble (a

private traditional performance group), the State Circus, which travels

around the world, and the State Morin Khuur Ensemble, which has also

enjoyed international and national success in recent years.

The flourishing of ballet and classic music development in the 1970s and

1980s was indeed a unique stage in the history of the national arts.

Some groups that thrived during socialism are now struggling. The

Symphony Orchestra, for example, only plays concerts by reservation. The

Mongolian State Philharmonics, an organization founded in 1972 which

was the face of Mongolian music abroad, doesn’t serve the same place in

the new society which encourages individual ventures.

There are three fully state-run organizations: State Academic Theater of

Opera and Ballet, the Academic Theater of National Drama, and State

Academic Ensemble of Folk Dance and Music. These operate regularly but

are dependent on the state budget. World classics are still displayed on

the Mongolian stage regularly, as well as Mongolian productions. In the

summer of 2003, a new opera premiered, “ChinggisKhaan”, by B. Sharav.

It teslls the story of ChinggisKhaan in his youth, and weaves

traditional Mongolian elements with Western classical opera.

TRADITIONAL MONGOLIAN SONGS

Mongolian music is a reaction to our surroundings and life. Caring

for a baby provokes melody. Seeing a calf being rejected, its mother is

convinced to return by singing. Seeing white gers spread across the

green pasture inspires a proud melody. Traveling a long way on

horseback, riding sets a pace, the pace delivers rhyme, and here again

the song is involuntary. Hurrying to one’s beloved, the heartbeat

composes another melody. The sources of song are endless. Birthdays,

weddings, national holidays, winning a horse race or wrestling

competition, celebration of the elderly, mare’s milk brewing, wool

cutting, cashmere combing, and harvest comprise an endless chain of

reasons for singing and dancing.

Through the ages, music has spread around Mongolia through home teaching

and festivities. Any family or clan event was a good chance for

musicians and singers to gather together. Coming from different areas,

most often representing different tribes, people had the opportunity to

perform, to learn from others and to take home a new melody or song. In

this way, the ancient patterns of various corners of Mongolia have been

preserved by local masters for the

whole nation.

Some specific types of Mongolian song are:

Labor song. These are melodies sung while working.

The hunter’s call attracts the animal by imitating its call in order to

select a specific type of animal and to hunt with certainty, without

wounding.

Various herder’s calls manage the flock by signaling to go to pasture,

return home, generate more milking, encourage insemination, bring a

mother back to her calf, and so on.

Buuvey song. A buuvey song is a lullaby, or any

sweet melody expressing a mother’s boundless love for her baby. “Buuvey…

buuvey… buuvey…” is repeated while caressing a child to make him or her

sleep. The melody may come from the heart of mother and be improvised.

There are also lullaby songs with legends already composed, learned by

the family and distributed to other families and generations.

“Uukhay” or “guiyngoon” song. These are encouraging

and provoking calls, connected with seasonal events. As warm days

arrive, mare’s milk flows and the horse race training reaches its peak,

the “guiyngoon” songs of little riders is heard in every direction. It

is followed by songs of victorious winners, be it a rider, a wrestler or

archery master. Fans chant the “uukhay!” encouraging song, which

roughly means “go ahead”.

Mongol Hoomii. Mongol hoomii involves producing two

simultaneous tones with the human voice. It is a difficult skill

requiring special ways of breathing. One tone comes out as a

whistle-like sound, the result of locked breath in the chest being

forced out through the throat in a specific way, while a lower tone

sounds as a base. Hoomii is considered musical art – not exactly

singing, but using one’s throat as an instrument.

Depending on the way air is exhaled from the lungs, there are various

ways of classifying hoomii, including Bagalzuuryn (laryngeal) hoomii,

Tagnainy (palatine) hoomii, Hooloin (guttural) hoomii, Hamryn (nasal)

hoomii, and Harhiraahoomi: under strong pressure in the throat, air is

exhaled while a lower tone is kept as the main sound.

Professional hoomi performers are found in only a few areas with certain

traditions. The Chainman district of Hovdaimag (province) is one home

of hoomii. Tuva, a part of Russia to the north of Mongolia, is also a

center of Hoomii.

Long song. Another unique traditional singing style

is known as Urtiinduu, or long song. It’s one of the oldest genres of

Mongolian musical art, dating to the 13th century. Urtiinduu involves

extraordinarily complicated, drawn-out vocal sounds. It is evocative of

vast, wide spaces and it demands great skill and talent from the singers

in their breathing abilities and guttural singing techniques.

Long songs relate traditional stories about the beauty of the native

land and daily life, to which Mongolians offer blessings. These feelings

are formed into majestic, profound songs, such as “The Pleasure Sharing

Sun of Universe”, “The Old Man and the Bird”, “The One and Only Real

Love”, “Sunjidmaa, the Beloved”.

Epics and legends. This ancient genre, enriched by

generations, combines poetry, songs, music and the individuality of each

performer. Singers may sing with or without a musical instrument. These

sung stories are told from memory and may have thousands of quatrains.

Such long stories are usually performed on a long winter night.

By combining stories, music and drama, herders organize a kind of home

school. The children, while playing various collective games with bone

and wooden toys, listen to the songs and learn about history, life and

folklore.

“Geser”, “Jangar”, “Khan Kharakhui”, and “Bum Erdene” are classic legend

and story songs. Each is a library of folk wisdom and national

heritage.

TRADITIONAL MONGOLIAN MUSIC INSTRUMENTS

Traditional Mongolian instruments include:

morin-khuur” (horse head-decorated 2-string cello)

modontsuur” (string instrument)

yatga” (psaltery-like horizontal string instrument)

limbe” (flute)

shudarga” (3-string sitar-technique instrument)

yochin” (multi-string horizontal instrument with echoing box)

khuuchir” (cittern-like string instrument)

tumurkhuur” or “khulsankhuur” (metal or bambuu leaf resonance based instrument)

buree” (trumpet-like instrument)